With evolving challenges, many leaders have turned to coaching to build their skills and find new approaches to work. In this blog, Jeremy Swain, independent adviser on homelessness and former CEO of Thames Reach, shares his experience of coaching and how it helped him to become a better leader.

It was a week from hell, but in retrospect a fortuitous one. First there was an acrimonious trustee board meeting, provoked by an inadequate set of board papers for which I was fully responsible. Then, as the week drew to a close, I laconically roused myself to review a vital funding application to find that my contribution would not, as I had anticipated, take an hour but half a day with the deadline looming. Later, in a moment of glacially frank self-reflection, I concluded that those around me deserved better.

I decided that I need an external coach or mentor - I wasn’t sure which. I wanted someone who had no formal authority over me or any organisational link which could inhibit me. I knew I required challenge and fresh perspectives. And someone who would not be phased by my glaring inadequacies, as I intended to be utterly honest when talking about myself.

I had a person in mind – a long-shot. I had experienced Gerard in action at a couple of management and leadership events for members of the Institute of Directors. I was not a member, but my organisation occasionally received free places when an event was not fully booked. I liked his style. He was knowledgeable, engaging and, importantly, when he responded to questions, he refused to be cowed by the certainty of some members of the audience who required him to agreed with them on the benefits of particular management or leadership approaches. Lastly, he appeared affable which, temperamentally, I need as I have a horror of earnestness.

On ringing Gerard and shamelessly asking if he would be my coach at a fee that I knew to be around a quarter of his usual rates, I was delighted to hear that he would coach me for free. He told me that he always had two charity people on his books at any one time as a contribution to the charitable sector and there was a space. He was peremptory and we quickly agreed a day and time. The venue was the Reform Club at 104 Pall Mall. That part appeared to be non-negotiable, but as the room there only costed £10, I willingly acquiesced.

Challenge and fresh perspectives

And so began a coaching relationship, metamorphosing into a mentoring one, that lasted for over 15 years. Gerard was inquisitive, determined and immensely good company. In truth, it was initially disheartening how easily he managed to unearth my areas of weakness; my poor planning, over-confidence about being able to compete tasks on time combined with an unwillingness to delegate. My attraction to the drama of engaging directly with people experiencing homelessness and tendency to find attention to governance matters a bit of chore. He didn’t want to dwell on what he thought I did well. He had asked me to speak to the Samaritans where he was a trustee on the challenges of working with the Blair administration and concluded, having witnessed my presentation, that I didn’t need coaching in order to be able to hold an audience. Rare praise.

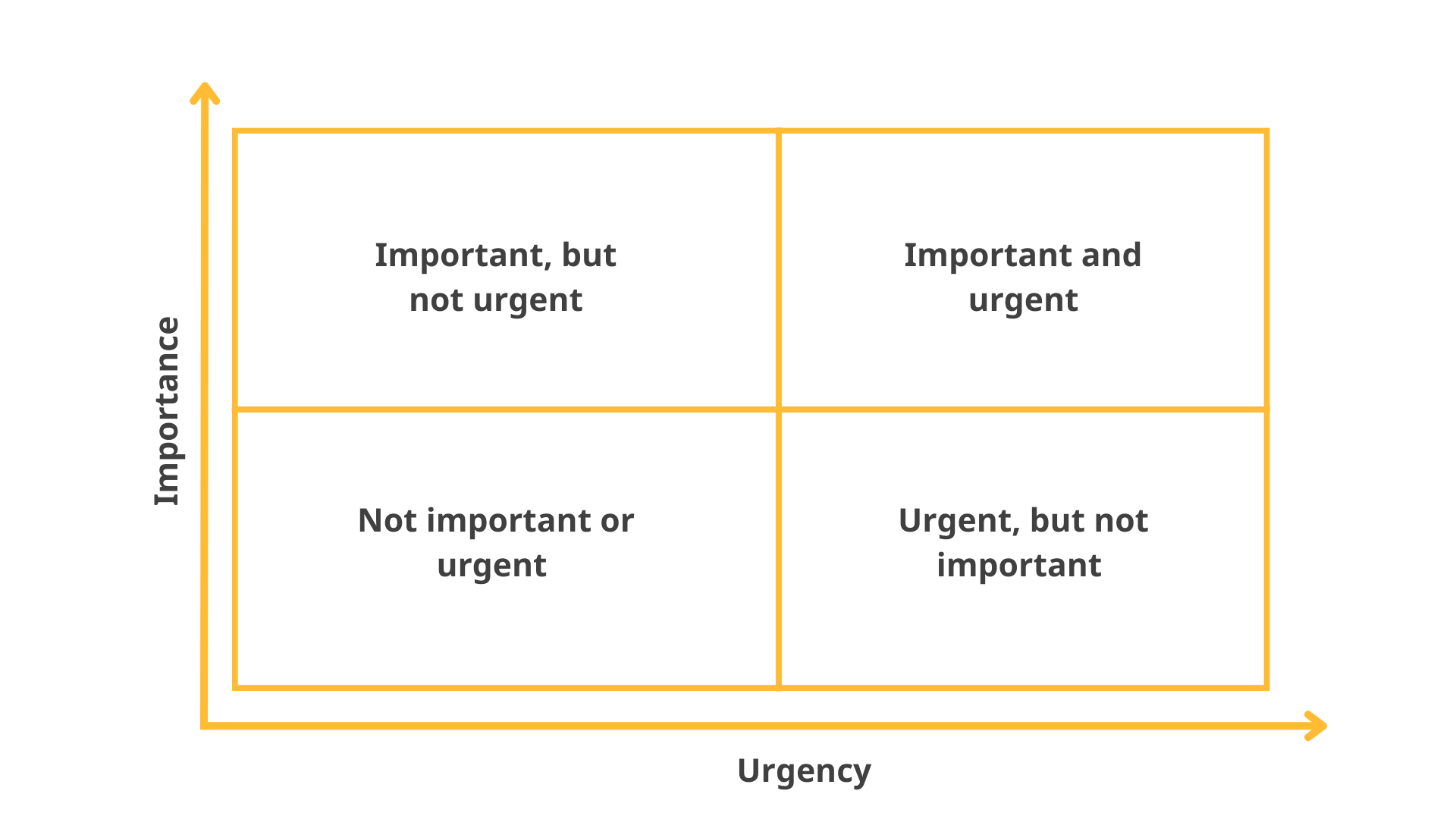

Gerard used a priority matrix with me relentlessly. All of our early sessions focused on this as he sought to drive me towards the important but not urgent. That damned upper left quartile began to haunt my working life. Sometimes I heard myself muttering ‘upper left’ as I forced myself to concentrate on the Business Plan, governance appraisal processes, strategies for engagement with key stakeholders, long-term financial planning or prioritisation of funding bids. He insisted that I block two half days a week in my diary to do the important but not urgent work. Pathetically, at times I hoped an important and urgent (upper right quartile) would emerge to shake up my week.

He was right, of course he was. I could see the organisation benefiting from my more organised and disciplined approach. As he annoyingly pointed out, ‘You, as Chief Executive are duty bound to do the things that only the Chief Executive can do’. This and other succinct guidance I retain so clearly. Another example was to try and delegate work as effectively as you do on the day before you go on holiday for two weeks; that is, with clarity and clear expectations. I could see that colleagues greatly preferred this to the previous version, typified by ambivalence about the task aligned with unspecified completion dates.

As I got to know Gerard an additional personal challenge emerged. I wanted someone different to coach me. I was nonetheless surprised when it emerged that he was a Conservative councillor. I vote Labour and regard myself as being left-of-centre. On reflection, despite believing the homelessness sector to be diverse, it did occur to me that I very rarely spoke to anyone in my working life who was socially or economically conservative in disposition or politically Conservative. Indeed, the only people with right-wing views who I conversed with regularly were some of my organisation’s service users who were often impressively articulate when it came to political debate. Somehow, this only led to me feeling more respect for Gerard and allowed us to start each session with some mock, yet serious, political jousting. What I never doubted was that Gerard had integrity.

From coach to mentor

At some stage, I can’t pinpoint exactly when, it became clear that Gerard had moved from coach to mentor. We met more informally, as and when I had specific challenges I wanted to think through. Then, around 2010 I hit a difficult period. The organisation was undergoing some retrenchment as a result of the banking crisis and the onset of the austerity period. The senior team had to make tough decisions about salaries, services and savings. My stress levels rose, and I found myself struggling to sustain myself as a 60-hour week became standard.

We had two excellent sessions entirely dedicated to dealing with stress which I found inordinately helpful. At the end I asked Gerard to recommend a good book on the subject. ‘I’ll send you mine.’ he said, ‘but ignore the chapter on coffee as the science now says it’s good for us’. His published book duly turned up in the post and is still there in my bookcase: ‘Stress Management – the Essential Guide to Thinking and Working Smarter.’ He was a modest man.

In 2018 I moved from the homelessness sector to the civil service and our meetings became less frequent. And then, as with many relationships, ours was fully ruptured by Covid-19. We met one last time when I took Gerard out for a meal in a central London restaurant. It was, of course, an entirely insufficient way of thanking him. We chatted cheerfully and I tried to express how important he had been to me, but he waved his hand at me dismissively, claiming that he was only ever just pointing me in the right direction. Which simply isn’t true. I miss Gerard and miss having a mentor. I like to think that I eventually became a half-decent Chief Executive, and for that I am forever indebted to him.